Living & Working with AI

Context for the Economics of AI at SF Tech Week

To close out SF Tech Week, I’m hosting a session on The Economics of AI — a chance to zoom out from the technical demos and product launches and look at the bigger picture. Researchers from OpenAI, Stanford, and others will present new data on how AI is reshaping productivity, automation, and the labor market. It will be small by design: short talks, a panel Q&A, and conversations over great coffee and pastries. Seats are limited — RSVP here

I’ve written before about AI at work — how it affects productivity, tasks, and decision-making. But broad adoption changes the kind of evidence we can rely on. For the past few years, most conversations were narrow: a study on call centers here, a coding experiment there. Useful glimpses, but they described isolated use cases. Without ubiquity, there was no way to see the larger pattern.

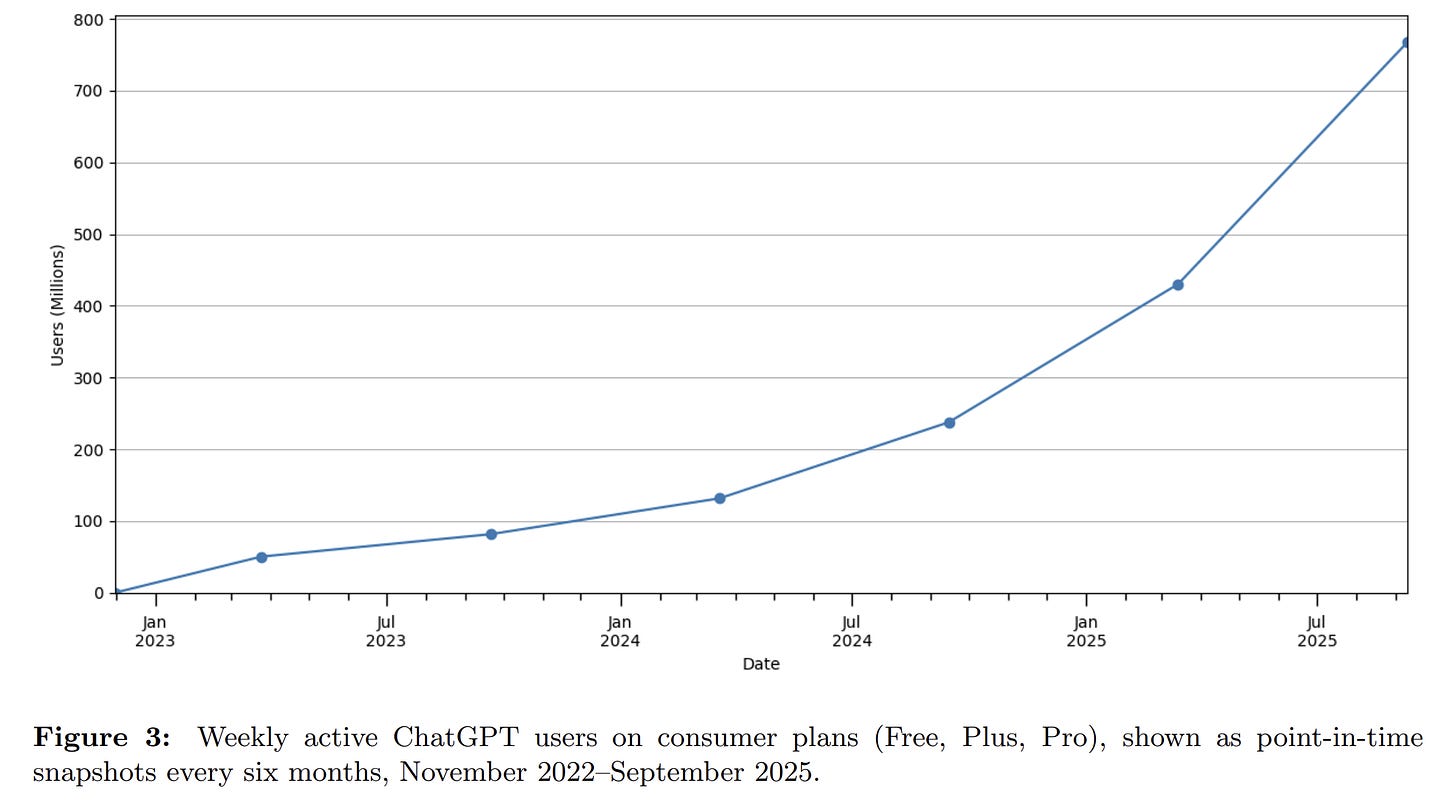

That’s shifted. ChatGPT now has more than 700 million weekly active users, sending around 18 billion messages each week. If current trends continue, it should cross 800 million by October. More than 70 percent of those interactions are outside of work. People use it for tutoring, recipes, fitness, or personal writing. That consumer side makes the scale visible, but the real question is what happens to work once AI is this embedded.

On average, each user sends about 26 messages a week, three to four per day. It’s no longer a trial tool. It’s routine. Think of the cadence: grocery shopping once or twice a week, coffee nearly every day, driving almost daily, checking a phone dozens of times a day. ChatGPT is not yet as constant as phone checks or text messages, but it has already settled into the rhythm of weekly life.

This is the turning point. Once a technology reaches that rhythm, we can stop speculating in fragments and start analyzing at scale. And the results for work are more complex than a simple story of automation. Customer support agents close tickets faster. Junior analysts complete more tasks in less time. Writing-heavy roles see measurable gains. But experienced developers in some trials actually slow down with AI, and productivity improvements depend heavily on task design and integration. AI is not just substituting labor — it is reshaping how tasks are done, who does them, and what counts as scarce skill.

That’s why it makes sense to revisit the economics of AI now. Not just through anecdotes or consumer adoption curves, but with benchmarks like GDPVal and studies that measure its impact on output and labor directly.

If you want to dig into that data, join us at The Economics of AI at SF Tech Week. We’ll look at how AI’s spread into everyday life and work is reshaping productivity, automation, and the labor market. RSVP here. Seats are limited so DM me or leave a comment if you’d like a seat.